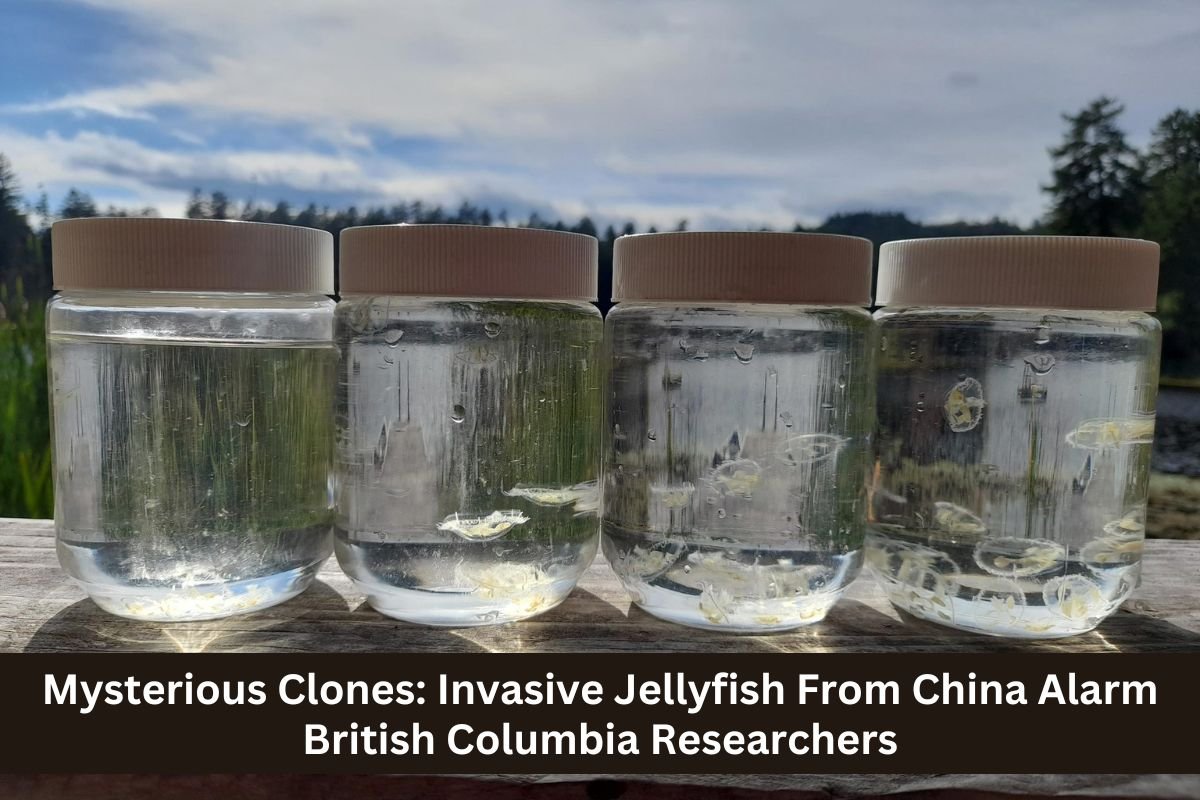

Researchers at UBC say that these clones could be harmful to local species because they are better at competing with them. A harmful freshwater jellyfish is showing up in large numbers in B.C. waters, and more sightings could happen very quickly in the future, according to study from UBC.

The peach blossom jellyfish has been seen in 34 places in B.C., which is the farthest north in North America. A new paper says that by the end of the decade, there will be even more sightings and more places to see them because climate change is making this range bigger.

Dr. Evgeny Pakhomov, professor in EOAS and the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF), and Dr. Florian Lüskow, who did the study during his postdoctoral fellowship at UBC’s Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS), talk about the strange jelly.

What do we know about these jellyfish?

FL: This type of jellyfish came from China and is now found all over the world. Canada’s ecosystems and biodiversity are being affected, but not much is known about this because the study hasn’t been done yet.

People are afraid that they will hurt native species by becoming too strong for them. With help from people in B.C., we are the only experts in Canada looking into these jellyfish.

Also see :- Top 5 frustrating zodiac signs

Since 1990, peach blossom jellyfish have been seen in British Columbia. They have mostly been seen in the Lower Mainland, on Vancouver Island, along the Sunshine Coast, and more lately, as far inland as Osoyoos Lake.

Over the 34 years from 1990 to 2023, 85 sightings have been recorded, with each place being counted once a year. Each sighting could have been of anywhere from one to thousands of jellyfish. But we think there will be about 80 sightings this decade alone, and most likely in more than the 34 places that have already been seen.

We know that all 100 jellyfish we’ve looked at so far have been male and have the same genetic material. This means that these thousands of jellyfish are basically clones that came from the same polyp or a small group of polyps, which is the stage of a jellyfish that lives at the bottom of a body of water.

EP: Polyps are hard to find because they are so small—usually about a millimeter across. They like to live in shallow water and can be found on rocks and wood that has been buried. So, we usually know that jellyfish have been introduced when we see the floating medusa shape that polyps make in the water.

These shapes only show up when the water temperature is above 21 degrees Celsius, which means that polyps could be in a lot more lakes than we know about. We don’t know how or when the species got there, but it probably came from medusa-making polyps being carried on leisure boats or on birds’ bills or feet when they ate.

We never saw medusae in creeks or rivers, but we did find them in ponds, mines, and lakes. Also, we know that jellyfish are safe for people because their bites can’t go through skin.

How is climate change affecting these jellies?

B.C. is the northernmost point of the peach blossom jellyfish’s range on North America. To have babies, it needs warm winters and hot summers. Since the winters are too cold in the Prairies, we wouldn’t see them there.

EP: We will likely see a bigger spread if climate change causes saltwater to warm up across B.C. Based on modeling, it looks like even Alaskan lakes could be invaded. One good thing is that only boys have been seen so far, and they are genetically identical.

This means that the jellyfish can’t have all of their sexual reproduction, which means they won’t be able to adapt as well to new habitats. Their spread would be slowed down by this.

What are the next steps?

EP: There should be two main goals. First, it’s important to make a correct picture of where the peach blossom jellyfish actually lives in British Columbia, including its range. Second, to get a better idea of how much jellyfish hurt freshwater environments, which includes young salmon.

Florida: To reach the first goal, we want to use environmental DNA, a tool that finds DNA in a sample of water. In this way, we could tell if the jellyfish is there even if we can’t see it, say, in its polyp form.